Popular articles

Azhar- Great university of Islam By Dr Khālid ibn ‘Alī ibn Muḥammad al-Mushayqiḥ

The Waqf bill controversy in India

The land of Khaybar: Waqf of ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb رضي الله عنه

Condolences on the Passing of Mawlana Qari Yusuf Ali Mangera (rahimahullah)

Reviving Waqf: A Legacy of Sadaqah Jariyah

Ibn Jubayr's Travels and the Remarkable Endowments He Encountered

The well of Rūmā (Bi’r Rūma)

The Waqf bill controversy

الحمد لله والصلاة والسلام على رسول الله

All praise is for Allāh ﷻ, and prayers and salutations on the Messenger of Allāh ﷺ.

Allāh ﷻ says in the Qur’ān:

إِنَّمَا السَّبِيلُ عَلَى الَّذِينَ يَظْلِمُونَ النَّاسَ وَيَبْغُونَ فِي الْأَرْضِ بِغَيْرِ الْحَقِّ أُولَئِكَ لَهُمْ عَذَابٌ أَلِيمٌ

Blame is only on those who wrong people and transgress in the land unjustly. It is they who will suffer a painful punishment. (Qur’ān; Sūrah al-Shūrā 41).

Al-Barā’ ibn ‘Āzib states that the Prophet ﷺ ordered us to do seven things and prohibited us from doing seven other things. (1) To pay a visit to the sick (inquiring about his health), (2) to follow funeral processions, (3) to say to a sneezer, "May Allah be merciful to you" (4) to return greetings, (5) to help the oppressed, (6) to accept invitations, (7) to help others to fulfil their oaths (Hadith; Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 2665).

Indian Muslims are currently facing an alarming surge in Islamophobia, manifested not only through grassroots societal hostility but also enshrined in state policies and official rhetoric. At the heart of this rising antagonism is the ascent of Hindutva, a Hindu nationalist ideology that envisions the transformation of India into a culturally and politically Hindu nation. This movement seeks to "reclaim" India by portraying it as a land whose true and original identity is exclusively Hindu, thereby marginalising religious minorities, particularly Muslims.

Within this narrative, Indian Muslims are increasingly framed as outsiders or interlopers, foreign to the fabric of the Indian nation. This revisionist view systematically erases or diminishes the rich and longstanding contributions of Muslims to the Indian subcontinent, whether in architecture, literature, language, governance, or spiritual thought. Centuries of shared history are being recast through a communal lens that pits Muslims against a homogenised Hindu identity, leading to policies and social currents that fuel discrimination, exclusion, and violence. As the title of this piece states, the focus will be about the Muslim practice of waqf and how it relates to the current controversy. Before we begin, the significance of waqf cannot be understated when it comes to the running of Islamic societies in the past. Wael Hallaq writes;

“This was because fundamental to the entire enterprise was the law and practice of waqf, a defining aspect of the cultural and material civilisation of Islam.

The law of waqf, therefore, represented the glue that could bind the human, physical and monetary elements together. Essentially, waqf was a thoroughly religious and pious concept, and as a material institution it was meant to be a charitable act of the first order. One gave up one’s property “for the sake of God,” a philanthropic act which meant offering aid and support to the needy. The promotion of education, especially of religious legal education, represented the best form of promoting religion itself. A considerable proportion of charitable trusts were thus directed at madrasas, although waqf provided significant contributions toward building mosques, Ṣūfī khānqāhs, hospitals, public fountains, soup kitchens, travelers’ lodges, and a variety of public works, notably bridges. A substantial part of the budget intended for such philanthropic enterprises was dedicated to the maintenance, daily operational costs and renovation of waqf properties. A typical waqf consisted of a mosque and rental property (e.g., shops), the rent from which supported the operation and maintenance of the mosque.”[1]

Waqf falls under the wider category of charity, a concept that Islam has made a fundamental component of every Muslim’s life. The Qur’ān describes the nature of charity:

مَثَلُ الَّذِينَ يُنْفِقُونَ أَمْوَالَهُمْ فِي سَبِيلِ اللَّهِ كَمَثَلِ حَبَّةٍ أَنْبَتَتْ سَبْعَ سَنَابِلَ فِي كُلِّ سُنْبُلَةٍ مِائَةُ حَبَّةٍ وَاللَّهُ يُضَاعِفُ لِمَنْ يَشَاءُ وَاللَّهُ وَاسِعٌ عَلِيمٌ

The example of those who spend their wealth in the cause of Allah is that of a grain that sprouts into seven ears, each bearing one hundred grains. And Allah multiplies ˹the reward even more˺ to whoever He wills. For Allah is All-Bountiful, All-Knowing. (Qur’ān; Sūrah Baqarah 261).

It is therefore no surprise that Muslims were and are so deeply committed to helping others, as it is a core principle of our faith and one that is strongly encouraged and rewarded.

A Brief Historical Background

The British East India Company (EIC) - a trading company chartered in 1600 - began its presence in the Indian subcontinent in the early 17th century, primarily for commercial purposes. Initially, the Company functioned under the suzerainty of the Mughal Empire, and was not permitted to interfere in local governance or legal systems. However, following its military successes—particularly after the Battle of Plassey in 1757—the Company transitioned from a commercial enterprise to a colonial power. From the mid-18th century onward, the EIC increasingly asserted political and legal control over Indian territories. One of its long-term aims was to restructure local legal and economic systems to facilitate open markets and unrestricted trade, which often meant overriding indigenous laws and customs in favour of legal frameworks that allowed the Company to maximise profit and exploit resources more freely.

It is well known that the nature of Islamic law facilitates flexibility. Islamic law has been represented by the Ḥanafī, Mālikī, Shāfi’ī and Ḥanbalī schools. These schools differ in many of their presentation of rulings. Furthermore, within each school there will be differences in nuances and application. The Muslim judges in each era could employ their understanding of their school in different ways. This flexibility restricts the control of the governing elite. So, one main goals of the colonial project was to categorise the orient and to establish clear codes of law, this will take the authority away of the Muslim judges. The eventual translation of Hidāyah of Imam Marghinānī into English allowed for the British colonial power to take direct control of Islamic law, excluding the middle-men ‘ulamā’ class. This class were those who interpreted and applied the law.

An example of state intervention and the perceived inadequacy of Islamic law can be seen in the laws governing homicide (dimā’). Under Islamic law, the right to determine the punishment traditionally lies with the next of kin, thereby limiting the state’s exclusive authority to adjudicate such matters. This right was eventually abolished during colonial rule. [2]

Moving to the specific case of waqf in India, despite the onslaught on Islamic law, Muslims were able to pass the Mussalman Wakf Validating (Act VI 1913). The Act begins with the following words:

“An Act to declare the rights of Mussalmans to make settlements of property by way of “wakf” in favour of their families, children and descendants.

Whereas doubts have arisen regarding the validity of wakfs created by persons professing the Mussalman faith in favour of themselves, their families, children and descendants and ultimately for the benefit of the poor or for other religious, pious or charitable purposes; and whereas it is expedient to remove such doubts; it is hereby enacted as follows;-”[3]

Ten years later, the Mussalman Wakf Act of 1923 was enacted. While the Wakf Validating Act had established the legal right of Muslims to create waqfs, the Mussalman Wakf Act was introduced to ensure the proper management and oversight of these endowments. It laid out specific procedures to regulate their administration and maintain their effective functioning.[4] A second Mussalman Wakf Validating Act was passed in 1930 which was merely expanding the 1913 Act to retrospectively validate previous waqfs[5].

The Wakf Act 1954 (Act XXIX of 1954) provided for the incorporation of Waqf Boards in every state. It also provided for the investigation, survey and registration of waqf properties. With the passage of this legislation, many of the State Acts were repealed[6]. Many other amendments ensued over the coming decades taking into consideration issues with the maintenance, the waqf boards and other related issues.[7]

The Waqf Act of 1995 marked a significant milestone in the legal and administrative history of waqfs in India. Spanning over 50 pages[8], the Act lays out a comprehensive framework for the effective management and regulation of waqf properties. It provides for the establishment of State Waqf Boards and a Central Waqf Council, tasked with overseeing the preservation, development, and lawful use of waqf assets. Most importantly, the Act reinforces the right of Muslims to freely practice their faith, ensuring that waqf institutions remain protected and aligned with their religious, charitable, and social purposes. An amendment was made to this act in 2013.

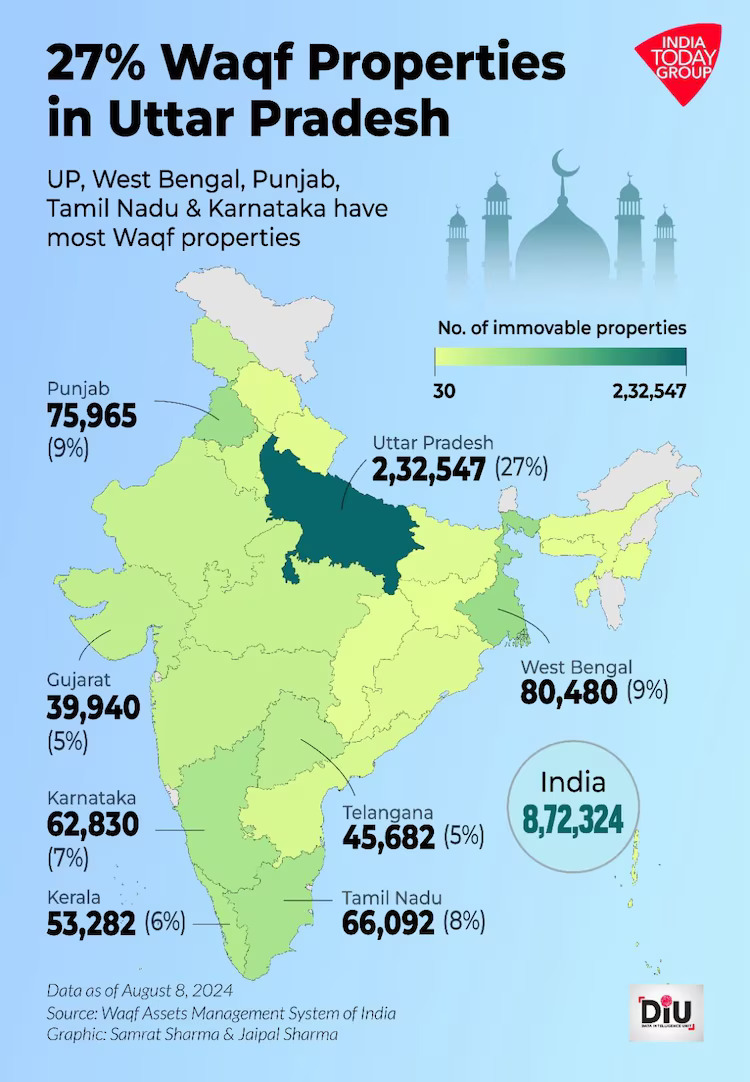

The result of these bills has allowed the preservation and establishment of many waqfs in India. The following graph highlights the number of registered immovable waqfs. The total number comes to 872,870[9]. Therefore, the significance of the waqf in India cannot be understated. Any attempt to shift policy will rightly be viewed with great scrutiny.

The current waqf repeal bill

It is a reality that there have been some shortcomings in the managing of certain waqfs. This has been recognised and various ‘ulamā’ have written recommendations on the responsible running of waqfs[10]. The current attempt to repeal the Mussalman Wakf Act, 1923 and the Waqf act,1995 has been presented in the Lok Sabha by the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) as a solution to the shortcomings of the running of waqfs. This bill restricts the practice of waqf by adding conditions like the Muslim must be practicing Islam for five years or the representation of Non-Muslims on Waqf boards. Beyond some of these conditions not coinciding with Islam law, it is the consistent Islamophobic rhetoric and practices of the Hindu Nationalists[11], why Muslims are viewing this through sceptical lens. Maulana Syed Arshad Madani, the president of Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, states:

‘How is it fair that the properties that belong to us be taken care of by someone else? This isn’t just a legal issue but a question of faith. We do not welcome any interference in our religious issues,

“if the constitution survives the country survive, if the country survives, we will survive”.

The fear is further justified when some of the rhetoric in regard to waqf is analysed. Anurag Thakur, from the BJP party and member of parliament, made the claim that the Beyt Dwarka Islands was being claimed as waqf by the Gujrat Waqf board[12]. The spread of fear and hate against Muslims is clear in this claim, as the Beyt Dwarka is claimed to be the residence of the Hindu God Krishna. The Gujrat Waqf board denied they ever made such a case[13]. Furthermore, it is widely seen that this will open doors for the potential to usurp awqaf under the pretext of mismanagement.

In light of the above, we at the National Waqf, an independent charity registered in the United Kingdom, affirm our unwavering support for the independence of Muslims in administering awqaf in India. Any reform or rectification efforts must respect the constitutional guarantee of religious freedom and avoid encroaching upon Islamic law. It is especially concerning when such actions come from parties with a documented record of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim bias, such interference will be condemned in the strongest possible terms. As the governing authority for all Indians, regardless of religion or ethnicity, the Indian government bears the responsibility to uphold the rights of every citizen. We remain hopeful that any forthcoming legislation will honour this commitment and uphold the centuries-old tradition of respecting waqf as a vital Islamic institution recognised by successive Indian administrations.

Written by Dr. Mawlana Zeeshan Chaudri

[1] Wael Hallaq, Sharīa: Theory, Practice and Transformation (New York:Cambridge University Press), p. 142.

[2] This overview is summarised predominantly from Wael Hallaq’s above cited work, Ibid, pp. 371-372.

[3] A scan of the Act can be found here (last accessed 16/04/2025).

[4] The Act can be read here (last accessed 16/04/2025).

[5] The Act can be read here (last accessed 17/04/2025).

[6] Munawar Hussain, Muslim Endowments, Waqf Law and Judicial Response in India (New York: Routledge) p. 31.

[7] Ibid, pp. 31-34.

[8] See here(last accessed 17/04/2025).

[9] See here(last assessed 23/04/2025).

[10] Waqf Role in Development (New Delhi: IFA Publications), pp.149-151.

[11] Rahul Bhatia’s recent work documents the spread of Islamophobic and anti-Muslim sentiment in India and how the ruling party has advocated policies which are clearly taking aim at the Muslim population, see Rahul Bhatia, The New India: The Unmaking of the World’s Largest Democracy (New York:Public Affairs).